A Few Don'ts for Those Beginning to Write Verse from Ezra Pound

21 AUGUST, 2012 by Maria Popova"Consider the way of the scientists rather than the way of an advertising agent for a new soap."

Say you've already learned how to read a poem, but now crave some verse of your very own. How, exactly, do you do it artfully?

Say you've already learned how to read a poem, but now crave some verse of your very own. How, exactly, do you do it artfully?

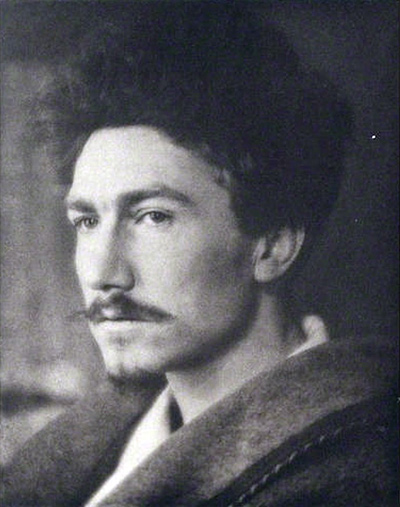

In 1913, Ezra Pound penned "a list of don'ts for those beginning to write verses" under the title of "A Few Don'ts by an Imagiste," which promised to "throw out nine-tenths of all the bad poetry now accepted as standard and classic [and] prevent you from many a crime of production." The short essay was part of Pound's "A Retrospect," outlining the principles of the imagist group, which he co-founded along with H.D., Richard Adlington, and F.S. Flint. It appears in Literary Essays of Ezra Pound (public library), originally published in 1918, with an introduction by none other than T. S. Eliot.

Pound begins with a piece of advice that applies as much to poetry as it does to the rest of life:

Pay no attention to the criticism of men who have never themselves written a notable work.

He then moves on to specific prescriptions for the use of language:

Don't use such an expression as 'dim lands of peace.' It dulls the image. It mixes an abstraction with the concrete. It comes from the writer's not realizing that the natural object is always the adequate symbol. Go in fear of abstractions. Don't retell in mediocre verse what has already been done in good prose. Don't think any intelligent person is going to be deceived when you try to shirk all the difficulties of the unspeakably difficult art of good prose by chopping your composition into line lengths. What the expert is tired of today the public will be tired of tomorrow. Don't imagine that the art of poetry is any simpler than the art of music, or that you can please the expert before you have spent at least as much effort on the art of verse as the average piano teacher spends on the art of music. Be influenced by as many great artists as you can, but have the decency either to acknowledge the debt outright, or to try to conceal it. Don't allow 'influence' to mean merely that you mop up the particular decorative vocabulary of some one or two poets whom you happen to admire. A Turkish war correspondent was recently caught red-handed babbling in his dispatches of 'dove-gray' hills, or else it was 'pearl-pale,' I can not remember. Use either no ornament or good ornament.

Next, he examines rhythm and rhyme:

Let the neophyte know assonance and alliteration, rhyme immediate and delayed, simple and polyphonic, as a musician would expect to know harmony and counter-point and all the minutiae of his craft. No time is too great to give to these matters or to any one of them, even if the artist seldom have need of them. Don't imagine that a thing will 'go' in verse just because it's too dull to go in prose. Don't be 'viewy' — leave that to the writers of pretty little philosophic essays. Don't be descriptive; remember that the painter can describe a landscape much better than you can, and that he has to know a deal more about it. When Shakespeare talks of the 'Dawn in russet mantle clad' he presents something which the painter does not present. There is in this line of his nothing that one can call description; he presents. Consider the way of the scientists rather than the way of an advertising agent for a new soap.

The scientist does not expect to be acclaimed as a great scientist until he has discovered something. He begins by learning what has been discovered already. He goes from that point onward. He does not bank on being a charming fellow personally. He does not expect his friends to applaud the results of his freshman class work. Freshmen in poetry are unfortunately not confined to a definite and recognizable class room. They are 'all over the shop.' Is it any wonder 'the public is indifferent to poetry?'

Don't chop your stuff into separate iambs. Don't make each line stop dead at the end, and then begin every next line with a heave. Let the beginning of the next line catch the rise of the rhythm wave, unless you want a definite longish pause. In short, behave as a musician, a good musician, when dealing with that phase of your art which has exact parallels in music. The same laws govern, and you are bound by no others. Naturally, your rhythmic structure should not destroy the shape of your words, or their natural sound, or their meaning. It is improbable that, at the start, you will be able to get a rhythm-structure strong enough to affect them very much, though you may fall a victim to all sorts of false stopping due to line ends and caesurae. The musician can rely on pitch and the volume of the orchestra. You can not. The term harmony is misapplied to poetry; it refers to simultaneous sounds of different pitch. There is, however, in the best verse a sort of residue of sound which remains in the ear of the hearer and acts more or less as an organ-base. A rhyme must have in it some slight element of surprise if it is to give pleasure; it need not be bizarre or curious, but it must be well used if used at all.

For more famous advice on writing, see Kurt Vonnegut's 8 rules for a great story, David Ogilvy's 10 no-bullshit tips, Henry Miller's 11 commandments, Jack Kerouac's 30 beliefs and techniques, John Steinbeck's 6 pointers, George Orwell's four universal motives for writing, Susan Sontag's synthesized wisdom on writing, and various invaluable insight from other great writers.

Then, wash down with Several Short Sentences About Writing.

Brain Pickings has a free weekly newsletter and people say it's cool. It comes out on Sundays and offers the week's best articles. Here's what to expect. Like? Sign up.

Brain Pickings has a free weekly newsletter and people say it's cool. It comes out on Sundays and offers the week's best articles. Here's what to expect. Like? Sign up.

kuşadası

ReplyDeletemilas

çeşme

bağcılar

çanakkale

3S0S5W