Lifecycle Strategy: How to Tell if You’re Doing it Right

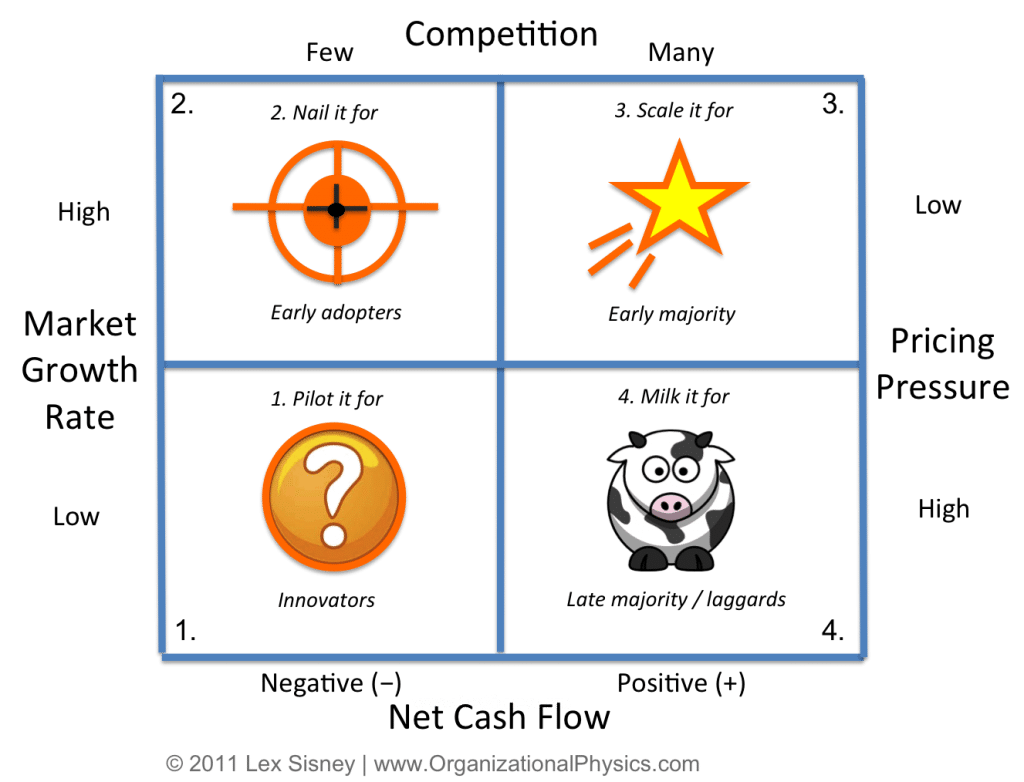

In my previous post, I introduced the product, market, and execution lifecycles and why a successful strategy must align them. Now we’ll take a look at the four key indicators that will tell you if you’re on the right strategic path. The key indicators, which must be taken into account at each lifecycle stage, are Market Growth Rate, Competition, Pricing Pressure, and Net Cash Flow.

Four key metrics guide the timing and sequence of your strategy: Market Growth Rate, Competition, Pricing Pressure, and Net Cash Flow.

Let’s take a visual walk around the figure above and see how the key indicators work. First, notice that when you’re piloting your product for innovators in quadrant 1 you should be in negative cash flow. The total invested into the product to date should exceed the return. The market growth rate should be low because you’re still defining the problem and the solution for the market. Therefore, the competitors within your defined niche should be few both in number and capabilities. Consequently, the pricing pressure will be high because you haven’t defined the problem or the solution, so you have no ability to charge enough money for it at this stage.

As you’re demonstrating thought leadership and winning over the innovators, you uncover the real business problem and begin to Nail It for early adopters in quadrant 2. Notice that you’re still in negative cash flow at this stage. It is taking considerable investments of time, energy, and money to fund early-stage product development. But as you progress, more and more early adopters jump on board and the market growth rate begins to increase. The competitors should still be few but, because you’re proving that you’re solving the customer problem, the pricing pressure lessens and you’re able to charge more for your product at this stage. That is, you no longer have to give the product away for free or cheap like you did at the prior stage because you’re showing that you do in fact solve a problem and add value.

As you’ve nailed the product in quadrant 2, you leap across the chasm into quadrant 3 and begin to scale the product for the early majority by standardizing it. The market growth rate should be high now and increasing. Also, the number of competitors entering the market will be growing because they see the increasing market demand and either think they have a way to do it better or are content to be a “me-too” competitor in a growing pie. Alternatively, they might feel they need to act to defend their existing turf. If you’ve done the sequence right so far, then you’ve established thought leadership at the Pilot It stage; you’ve proven that you’ve solved the problem at the Nail It stage; and you’ve standardized the product early in the Scale It stage, which increases your margins. Now is the time to add new high-value extensions and add-on products and services that increase the life and perceived value of the product in the marketplace. This will help you avoid the final product/market stage, the commodity trap in quadrant 4, for as long as possible.

Because you’ve done the sequence right so far, you should be in a market leadership position and the pricing pressure, even though there’s a lot of competition, should still be low for your product in quadrant 3. Just think of how, in spite of many iPhone competitors, Apple still keeps the price of its iPhone high relative to the competition. Others can compete on price but Apple doesn’t have to yet until the market is in a true commodity phase. In this stage, you’re finally in positive net cash flow for this product and you’ve got standards, leadership, and demand. All of your hard work should be paying big dividends.

Quadrant 4 is known as the “commodity trap.” Your goal is to avoid this commodity trap for as long as possible by continuing to create high-value product extensions in quadrant 3. But when you ultimately arrive at quadrant 4 (all markets ultimately do), the market growth rate is slow because the fundamental problem has been solved for most customers. For example, if everybody has an iPod, there’s no longer a growth market for the product. During the preceding stages, a lot of competition has emerged and they are still attempting to compete, often on price. Consequently, the pricing pressure is really high. Despite these challenges, if you’ve done the preceding product/market sequence correctly, you have a cash cow that can “print money” until it must finally be sold or killed off.

The Path to Prosperity: Doing It Right

Understanding how to align the product/market/execution lifecycles reveals the path to strategic success. It goes “the long way around,” as depicted in the figure below. Basically, if you pilot your product for innovators, nail it for early adopters, and scale it for the early majority, then you create maximum building of market awareness; you make smart, timely investments relative to market readiness; you maintain pricing and margins; and you avoid the commodity trap for as long as possible. That’s the path to prosperity.

Just because success requires taking the long way around doesn’t necessarily mean that it has to take a long amount of time. As the late John Wooden said, “Be quick, but don’t hurry.” There’s real, hard work to be accomplished. It needs to be completed in the right sequence and there will be many ongoing, necessary adjustments to the strategy but no matter what, you have to follow the sequence. No skipping, no shortcuts, and no racing ahead before it’s time.

Investment Capital: Timing and Sources

One of the greatest concerns for entrepreneurial startups is when and how to get financing for their business. Financing from external sources is always required to successfully navigate the product/market lifecycle from start to finish. “External” simply refers to sources other than the product itself. For example, when a product is in the Pilot It and Nail It phases, it generates negative net cash flow. It will need additional financing to make it to scale. Or, when a product is in scale mode, it may need more capital sources to fund expansion, staffing, and aggressive sales and marketing. Different types of external financing sources are leveraged at different stages. If this is a new product launch funded within a parent company, then the parent takes on the burden of funding the new product until it is in scale mode and generating positive net cash flow. But as an entrepreneur, it is helpful to recognize in advance which type of external financing usually participates at each stage of the product/market/execution lifecyles.

Pilot It Stage (Starting in Quadrant 1)

Financing early in the Pilot It stage is usually a combination of self-financing and the contributions of friends and family. The entrepreneur takes out a loan, invests proceeds from a previous venture, or gets friends and family to participate as early investors. Note that friends and family invest because they trust the entrepreneur, not because the business proposition and path to exit are clear at this stage.

Pilot It to Nail It Stage (Moving from Quadrant 1 to 2)

Angel investors usually participate between the Pilot It and Nail It stages. This occurs because a product prototype has been developed (this could be as simple as a PowerPoint or screenshots) and the business case is significantly clearer than at the prior stage. Angel investors are willing to take tremendous risk in exchange for a lower valuation on the company and most will seek to help the company figure out how to really nail the product and ultimately get it ready for scale and future investors.

Nail It to Early Scale It Stage (Moving from Quadrant 2 to 3)

Venture capital (VC) investments usually take place between the Nail It and early Scale It stages – once the company has demonstrated that they have nailed the product and understood the market problem and when market demand is clear and the company needs capital to scale. The VC will offer capital and access to resources such as staff, market connections, and expertise to scale the business. Their focus is to invest at a low enough valuation that can generate a significant return on investment later on through a sale of the company or an initial public offering (IPO).

Corporate investors also participate at this stage but for different reasons than VCs. They invest to acquire rights or interest in a promising technology that fits their own strategic roadmap. This type of technology acquisition gets a lower valuation than if the company had scaled itself into a profitable growth mode. Often a smaller company with patented and/or promising technology will seek to sell to a much larger company at this stage so that the founders can create liquidity and the new parent company can leverage its larger sales, distribution, and customer support staff to support the rollout of the acquired technology into scale.

Scale it Stage (Moving across Quadrant 3)

Once the company enters its scale mode and is generating significant cash flow, and if it has a clear opportunity to capture a significant market opportunity, then it will do one of three things to get external financing. One, the company will do an IPO. Two, the company will sell itself to a larger company. In this case, the valuation is usually much higher than the previous technology-only acquisition because the acquirer is buying more than just a technology – it is also buying the future cash flows, profits, and budding brand awareness of the seller. Or three, the company will choose some type of bridge or mezzanine financing that helps to bridge the financing gaps that appear when a company is attempting to scale up but isn’t ready for an IPO or strategic sale yet.

Milk it Stage (Moving from Quadrant 3 to 4)

This stage is less about business growth and more about cost cutting, roll-up acquisitions, and financial engineering. Private equity groups use their war chest and access to cheap capital to acquire other companies that can be repackaged for a future sale. Large corporate acquisitions are made as well, but it’s usually for the cash flow that the businessess generate or for the existing patents, customers, or distribution channels. How Wall Street reacts to the deal is usually viewed as more important than the fundamental business principles at work. Radical new innovations that are required in the prior stages are viewed as distractions to be avoided in this stage.

What About Customer-Driven/Agile Development?

Within high-tech entrepreneurship circles today, “customer-driven development” or “sell, design, build” is all the rage. These approaches were brought forth by authors like Stephen Blank of Four Steps to the Epiphany and product development consultants like SyncDev in Santa Barbara, California, as well as trends around growing adoption of agile software development methodologies. It’s worth commenting on how these approaches fit into the product/market/execution lifecycle scheme we’re discussing.

Essentially, what the customer-driven development school recommends is that an entrepreneur go as far as possible from the start of quadrant 1 (Pilot it for Innovators) to the top of quadrant 2 (Nail it for Early Adopters) by interviewing, researching, and selling customers in advance before the product development process begins. That is, they’re trying to limit the cost, risk, and time investments of making poor product or market decisions between the Pilot It and Nail It stages. They are looking for a good product/market fit before the development process begins. If they can discover what the thought leaders really value and what the early adopters’ true spending priorities are before development begins, this lowers the risk and increases the probability of meeting those needs. Development can become more focused and demand is established before any real money is spent on development.

Agile software development is a product development method that aligns very closely with a customer-driven philosophy. Agile, or iterative, development is a process of taking real-time data from actual use of the product and quickly iterating changes using short release cycles to develop a better product that meets the needs of target customers. Fundamentally, agile is a product development method that attempts to better manage changing requirements, avoid long release cycles, and to produce live, working, tested software that has real business value. In an early stage startup, using an agile approach can help a company quickly and cost effectively navigate the Pilot It to Nail It stages by eliminating the guesswork, long product release cycles, and overhead involved in trying to do a big product design up front. In larger companies with existing products in scale mode, using agile is an attempt to better meet user requirements, based on data and customer feedback, and to turn that knowledge more quickly into new product features and extensions.

Having built several successful high-tech products and run agile development teams, I can say that I am a big fan and believer in both approaches. They go hand in hand. However, I want to be clear that these are just methods or approaches. Their real but unstated goal is to help a company navigate the path to prosperity more quickly and/or cost effectively. These approaches can help verify that your thinking is sound, that you’ve uncovered a proven market opportunity, and that demand is there. And as it relates to raising capital, having evidence that your entrepreneurial vision is baked in the cold, hard light of reality can make all the difference in getting the cash you need. They are sound methods and they fit perfectly well into the strategy lifecycle scheme.

The truth is that there are many other methods or approaches that can also help you quickly navigate the path to prosperity. Customer-driven can work. So can vision-driven. For example, I don’t believe Steve Jobs had ever done a day of listening to focus groups in his entire life. Instead, he had that rare ability to envision something entirely new, intuitively understand the needs of his target customers even before they did, and bring it to the world in surprising and beautiful ways. No external customer-driven development of the iPad would have worked because customers would have had no frame of reference for it. Walt Disney was the same way. He had a powerful vision and followed his own instincts about what families really valued that wasn’t being provided by other amusement parks at the time. He created magical experiences that no one was expecting. The point is that there are many ways to navigate the path to prosperity but the fundamentals are always the same: you must go the long way around the path and create the product/market fit in the right sequence.

نقل عفش بالباحه

ReplyDeleteنقل عفش بعسير

نقل عفش بالمجمعة

نقل عفش بشرورة